Identification

There are two species of bear in Alberta—the more common black bear (Ursus americanus), and the larger, but range-restricted grizzly bear (Ursus arctos). To fully enjoy bears in Alberta, one must understand and appreciate the differences in habitat use and habits of the two species. Camping, hiking or working in wild country can lead to close encounters with bears, and because each species may react in a different way, it is important to know how to tell them apart. Size and coat colour are not good distinguishing features. Although grizzly bears are generally larger than black bears in each sex and age, adult black bears can be larger than young grizzlies. Both species can range in colour from blonde to black. Under field conditions, bears are rarely in plain view; usually they are partially hidden by shrubs, trees or rock.

Distinguishing Features of Bears and Their Signs

| Feature | Grizzly Bear | Black Bear |

| Colour | May have silver or light-tipped guard hairs on head, hump and back | Uniform colour |

| Hair | Shaggy, varied lengths | Uniform and smooth |

| Ears | Rounded; appear smaller overall | Somewhat more pointed and noticeable |

| Nose | Pig-like | Dog-like |

| Claws | Long (-3-4 in.); may have light strip | Short (-1 in.) and usually black |

| Face ruff | Present | Usually absent |

| Chest spot | Absent | Present in some |

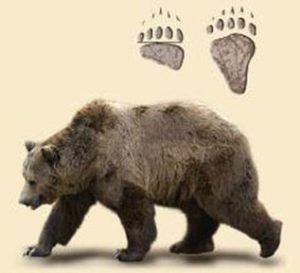

| Tracks | Front claw marks 2 to 3 in. in front of toes Width of front pad can be greater than 6 in. Toe arc lesser (see illustration) | Claw marks close to toes Front pad rarely over 5 in. Toe arc greater |

| Diggings | Common | Uncommon |

| Hair | May have banding and silver tips | Solid colour |

| Carcasses | Buried in debris | Seldom buried |

If you know how to look for bear sign, you will find it in abundance. Tracks, especially if made in mud or snow, are commonly observed. Other bear signs include walking trails, scats, rolled logs or rocks, torn stumps, rubbed, chewed or claw-marked trees, beds and diggings. Following these signs is entertaining and educational, but must be done with caution and common sense so as not to unduly disturb the animal or put yourself in danger by getting to close.

The two species leave a different kind of track. In soft ground, the claw marks of black bears are sharply incised and are close to the toe marks; whereas, with grizzlies, the claw marks, especially of the front loot, are slight, often difficult to see, and well ahead of the toe marks. You can measure the width of the front (pad) track to help identity the bear, but because there is much overlap in size between species, sex and age of bears, consideration of pertinent factors is necessary. For example, in country where only black bears are known to occur, a track in excess of 5 inches wide is a large male. In grizzly country, front tracks greater than 6 inches wide are likely of that species.

Bears are creatures of habit. They return again and again to familiar areas and by stepping in their own tracks, leave a trail with indentations in the ground that may endure for years. Such trails may lead to favourite rub trees or food sources. The long claws of grizzlies can scoop up leaves into little piles.

When travelling in forests where ground cover is heavy, the first noticeable signs of a bear may be a log rolled over onto grass or other vegetation. The bear turned the log to search for and feed on insects sheltered below. Similarily, an old stump torn to shreds indicates that a bear fed on ants, other insects or their larvae.

Bear scats may be round (2 to 3 inches in diameter) or, as is more often the case when a bear has been feeding on fresh greens such as horsetail or sedges, the scat may be patty- or pie-like, but still obviously bear. You can examine these scats to identify the foods con¬sumed by the bear.

Rubbed and chewed trees can show interesting details. Close examination may reveal countless hairs stuck in the sap or bark where the bear has rid himself of excessive winter hair or eased an itch. Most such trees will have chewings and some, bite marks at the height of the standing bear. Tall aspens will retain the claw-marked trail of a climbing black bear for the life of the tree, and these well-marked trees are often at intersections of forest trails.

Bears make beds or scrapes on the ground surface. Such “day beds” are slightly scooped into the ground or may be lined with boughs of conifers. If you are in bear country in spring (when bears are just leaving winter dens) or in fall (when bears are about to enter dens) do not go to sleep in the bear’s bed as you may soon have company.

Grizzly Bears

- Grizzly bears have a pronounced shoulder hump.

- Grizzly bears may have silver or light-tipped guard hairs on their head, hump and back; black bears may appear more uniform in colour. Both species can range in colour from blonde to black.

- A grizzly bear’s ears are rounded and appear smaller over all, while the black bear has more pointed and noticeable ears.

Black Bears

- Black bear claws are relatively short (approximately 2.5 centimetres in length), and are usually black. Grizzly bear claws are longer (approximately 7.5 to 10 centimetres in length); grizzly claws may have a light-coloured strip.

- Black and grizzly bear tracks differ significantly, although in mud or snow the tracks may be indistinguishable. The tips of the front claws usually

leave imprints a few centimetres in front of the front pad imprint.

Bear Signs

Tracks

• Grizzly tracks are typically larger than those for black bears (see Bear Identification on preceeding page).

• Bear trails – bears are creatures of habit and return to familiar areas; they sometimes step in their own tracks, leaving a trail.

Scats

• Bear scats are distinctive piles, especially following a diet of berries. Diggings

• Rolled logs and rocks – bears search for insects to eat under these items

• Torn stumps

• Rubbed, chewed and claw-marked trees

• Anthills torn open

• Well-buried carcass of large mammal, such as elk, deer, moose and cattle

• Concentration of scavenging birds, such as ravens, magpies and crows at a carcass

Understanding Bears

There are a few key characteristics and behaviours that must be understood regarding bears:

• Bears have a curious, investigative nature, an important trait that helps them find new food sources;

• Bears have an acute sense of smell, and they rely heavily on it to find food and other animals;

• Bears are intelligent. They figure out how to gain entrance to containers, vehicles and buildings that smell attractive to them, and they remember these skills;

• All bears are naturally wary of people and are reluctant to come close to people and human environments;

• All bears have personal space around them and feel scared or threatened when this space is invaded;

• Bears that have repeated contact with people with no negative experience may learn to tolerate people;

• A bear that has learned to associate food with people will actively search for food or garbage in areas frequented by people; and

• Most importantly, a bear’s life revolves around food. all bears are naturally wary of people

Black bear from AB bearsmart

http://aep.alberta.ca/fish-wildlife/wild-species/mammals/bears/black-bear.aspx

Grizzly bear from AB bearsmart

http://aep.alberta.ca/fish-wildlife/wild-species/mammals/bears/grizzly-bear.aspx

Bear ID quiz from AB bearsmart

http://aep.alberta.ca/recreation-public-use/alberta-bear-smart/know-your-bears/bear-identification-quiz.aspx

Biology & Ecology

Biology is the study of living organisms. Ecology pertains to the interrelationships between organisms and their environment. If we want to coexist successfully with bears and if we want to increase the pleasure of watching them, it is essential that we develop some basic understanding of their biology and ecological relationships to their habitat and to other animals.

Black Bears

The black bear is the smallest of North American bears. Body weights of adult males average 100-150 kg (220-330 Ib) and adult females average 70-100 kg (150-220 Ib), but there is much seasonal, and regional variation. Individuals in excess of 275 kg (600 Ib) have been reported. Bears are long-lived (up to about 30 years) and are not fully grown until 5¬6 years of age.

Historically, the black bear was widely distributed in suitable habitats throughout most of North America. It evolved as a forest-dwelling species and under natural conditions is shy and secretive, rarely venturing far from the security of forest cover. It is an expert tree climber, an ability young cubs learn soon after leaving the first winter den where they were born. Their short, curved and sharp claws are a great asset when they climb trees to find food and to escape danger from enemies on the ground. Their evolution in the forest environment included the use of open areas for feeding, but needing to occasionally flee from an enemy, resulted in an agile bear, capable of running up to speeds of up to 45 km/hr over short distances. They are good swimmers.

Most female black bears in Alberta do not become sexually mature until their fourth summer. In habitats where food is abundant, successful breeding may occur one year earlier. The resulting blastocyst does not implant until soon after denning in fall. The cubs are born about three months later, in January or February, inside the confines of the winter den. They are hairless and tiny weighing no more than two pounds, and their eyes remain closed for a week or so. The litter contains from one to four cubs, most often two. Implantation may be prevented in bears that have failed to store a sufficient supply of fats to support themselves and their young through the denning period.

In northern climates such as Alberta, black bears escape severe winter weather and food shortages by hibernating. During this period of dormancy, body temperature is lowered by 7¬8%C, metabolism is reduced 50-60 percent, and heart rate drops from 40-50 beats per minute to 8-19. Research by William Tietje showed that black bears in Alberta spend 5 to 6 months in winter dens and lose 10 to 30 percent or more of their body weight. They do not eat, drink, defecate or urinate during the entire denning period and the intestinal tract becomes blocked with a fecal plug unlit the bear emerges in spring.

Grizzly Bears

Grizzlies are large and powerful bears. An adult male grizzly in Alberta averages 180 kg (400 Ib), but may reach 325 kg or more in the better habitats. Like black bears, the female grizzly is about two-thirds the size of the male.

The grizzly bear evolved in the near- and post-glacial, mostly treeless habitats of the Pleistocene (last 2 million years of recurring ice ages). It adapted to a variety of open environments such as grasslands, arctic and alpine tundras, ocean beaches and river shorelines. Thus grizzlies today have long front claws which, in combination with massive shoulder and back muscles, allow them to dig rapidly in the soil. Grizzlies often feed on burrowing small mammals such as marmots and ground squirrels common in open areas. The post-glacial habitats, rich in prey, allowed the grizzly to grow to its large size as opposed to the black bear which remained in the more impoverished forests of the ancestral bear. In the absence of trees as an avenue of escape for its cubs, the mother grizzly developed an aggressive attitude in defense of her young more so than the black bear.

At one time, the distribution of grizzly bears was quite similar to that of one of its important prey items, the ground squirrel. Historically, grizzlies occupied the northern and inland tundra and prairie zones and occurred in most of the open western plains from northern Mexico to the arctic.

The reproduction of grizzlies is similar to that of black bears, except, that females do not breed until they are 5 to 7 years of age; most common litter size is two. Additionally, young grizzlies remain with their mothers one year longer (28-29 months) than young of black bears (16-17 months). As a result, female grizzlies, on average, breed only once in 3-4 years, less than their more productive black cousins (every 2 years).

Like northern black bears, grizzlies hibernate for the winter, although the period spent in the winter den averages slightly less. Usually the grizzly digs its den on a slope where the ground is stabilized by root systems of trees and shrubs and where accumulation of snow adds insulation. As a rule, grizzlies enter dens during a major snowfall (late October for females, late November for males).

Feeding Behaviour & Foods

Much of the following general summary of feeding behaviour is taken from the published works of Stephen Herrero, University of Calgary, who explained the evolutionary divergence and resulting differences in feeding strategies of black bears and grizzly bears.

Evolving from small, carnivorous, tree-climbing mammals, the earliest bears were forest dwellers that became opportunistic omnivores; they ate meat when it was available, and when it was not, they subsisted on vegetable matter. Because plant foods were more dependable than animal foods, highly digestible forbs, leaves, roots and fruits came to dominate the diets of bears. Quite late in their evolution, the ancestors of the present grizzly bear began to adapt to more open habitats; digging for foods such as ground-burrowing rodents as well as the roots and tubers of plants became a specialization of this species.

Both species have a relatively unspecialized digestive system which is essentially a carnivore’s gut that has been lengthened. Bears have no cecum and their stomachs are too acidic to support the microflora and microfauna needed to digest cellulose. They, therefore, have difficulty in digesting the woody parts of plants, but both species can still survive on a very high proportion of plant foods in their diet. They choose food items that are easy to digest such as berries (sugar), roots (starch), meat, protein-rich, rapidly-growing parts of plants, and fats (plant or animal).

Both species of bear choose the most digestible, nutritous foods which are available at a given time. When plant protein is a major item in the diet, its relatively low digestibility is counterbalanced by large intake. Grizzly bears effectively exploit foods in the soil; black bears in and around trees. However, there is still a great deal of dietary overlap between them. Grizzlies likely have a competitive advantage in open habitats, partly because of these feeding adaptations, larger size and greater defense of young.

Foods of The Black Bear

Research by Anne Holcroft (Kananaskis Country) and Brian Pelchat (Cold Lake) reveal that the diet of black bears varies with the seasons. On emergence from the winter den, a black bear is lucky if it discovers the carcass of a winter-killed animal; fortunate is the bear that finds a dead moose, but a floating beaver carcass or fish will do. In mountainous habitats, overwintered bearberries are favorite early foods. In the boreal forest, as the last snows melt in spring, the first green-up takes place far above the ground, and black bears climb tall poplars to feed on the sprouting new buds.

Gradually, the green-up on the forest floor provides other choice foods such as horsetails and sedges in shallow retreating waters, and dandelions along openings and roadsides. Peavines and clovers become popular as the grazing black bear roams farther and farther from the winter den. Some individuals bears, especially large males, will hunt for newborn calves of moose and caribou.

As spring turns to summer, an even wider variety of foods become available, including sarsaparilla, peavine, and especially ants and other insects. Wandering about the woods, bears overturn logs, tear apart stumps and occasionally try to catch a fish in streams or lake shallows. Berries are the staple during late summer and fall. In the mountains, the red buffaloberries are the usual favourites, but in the boreal forest, blueberry and other berry patches attract bears from mid July to early October.

In years of berry failures, which are locally fairly common, black bears find it difficult to sufficiently fatten for the coming long period of hibernation. Then they wander great distances and may succumb to human-related foods and get into trouble with people.

Foods of the Grizzly Bear

Grizzly bears use a wide variety of foods that differ significantly between mountain and boreal forest habitats. Individual diets range from almost totally vegetarian to a heavy depen¬dence on animal protein. Much of the following information on what grizzlies eat is taken from the works of Alberta grizzly biologists David Hamer, Stephen Herrero, John Kansas, John Nagy and Dick Russell.

When the first grizzlies emerge from their winter dens in late March or April, finding something to eat is a challenge. Snow still lies deep in valley bottoms and on north-facing slopes. South-facing and wind-blown steep terrains at lower elevations provide over-wintered bearberries, roots of Indianpotato (Hedysarum) and the earliest green shoots of grass. Dick Russell, who conducted the first comprehensive field study of grizzlies in Alberta, and Jack Nolan found that the roots of Hedysarum were essential spring foods in Jasper National Park. As spring turns to summer, horsetails, grasses, sedges, and the young of elk and moose become important. Some individual grizzlies intensively search for newborn calves in late May and early June. As spring matures, grizzlies slowly follow the ripening of plants up the valley slopes.

Horsetails remain part of the diet during June. But, as summer progresses, grizzlies switch to ants in dry, open south- and west-facing forests and old burns and to succulents like cowparsnip and glacier lily, found on moist avalanche slopes and in other wet areas. During summer, early berries become the preferred food. Buffaloberry, huckleberry and blueberry are all favourites, but many other species are used. These berry plants are most common in burns and on open sunny slopes.

In fall, late-ripening berries such as crowberry and low-bush cranberry increase in importance. As well, grizzlies of the mountains dig for the roots of Hedysarum and for ground squirrels. These two favourites are not available in the boreal forests east and north of the Rocky Mountains. Here, the grizzlies often forage in areas where grasses and clover have been seeded along roads and pipeline rights¬of-way.